Imagine you were going somewhere important, and you hit a roadblock. Maybe the construction crew was fixing gas lines that ran under the asphalt, making the road impassable. Would you turn around and go home?

No, you probably wouldn’t. You would put your GPS on and follow the detour to reach your destination.

It may take a little longer, and you may have to change course a couple of times, but you will get there. You may even discover a new part of town you’ve never seen before.

When we consider the concept of failure and apply this scenario to our lives, we can see much in common.

When you meet the roadblock face to face, you have the opportunity to reframe this perceived failure and think positively. It seems like a radical concept, but you can’t fail with this approach. This article aims to uncover the psychology behind the feeling of failure and discover why the perception, rather than the reality, holds us back. Read on.

The Illusion Of Failure

What is failure? And why are we so fixated on labeling any deviation from the expected path as a failure? The concept of failure casts a shadow of doubt and discouragement on our endeavors. It can stop people from ever trying anything new.

We start with big aspirations when we embark on our health and wellness journey. It often begins as a New Year’s resolution because that’s the time we feel the change will finally stick. I’m going to lose 100 pounds! I’m going to run a marathon! But halfway through the year (sometimes sooner), we find ourselves off our intended track.

After we’ve felt like we’ve failed “enough,” we start to avoid doing new or challenging things. Our brain (looking at you, habenula) tries to protect us from feeling like we’ve failed and actively works against us trying to make a change.

The habenula is our motivation kill-switch, and it works hard to keep us “comfortable” in our status quo – it’s a survival mechanism. It is thought to be responsible for influencing the brain’s response to everything from pain, stress, and anxiety to sleep deprivation and reward processing.1

How do we create lasting change if the habenula works so hard to “protect” us?

Unwire To Rewire: The Path To Transformation

Ever wonder how circus elephants are taught not to run away? They’re massive, majestic animals and significantly out-size any of their handlers. Yet they never stray too far. That’s because they are taught at a young age that they aren’t to leave their designated spaces, often by (painful) physical measures.

Even as these elephants grow in age and size, they don’t challenge their confines because they understand there may be consequences on the other side. Just like elephants conditioned by past limitations, we, too, hold on to beliefs that anchor us to our comfort zones – even if they are detrimental to our health and well-being.

Our brains become insecure when we try to chip away at our beliefs, causing us to revert to our old, comfortable ways. We must break down this barrier – the fear of failure – and challenge the beliefs that hold us back from lasting change.

The Filter Of Beliefs

Our beliefs act as filters, determining what we pay attention to and what we disregard. They have an immense impact on how we navigate the world. In that same vein, our brains really like confirmation bias – the human tendency to seek out, interpret, and remember information that confirms our beliefs.

Our brains actively seek out the information that confirms what we believe to be true while entirely ignoring and dismissing contradictory evidence. This bias is powerful – it can lead to a cycle that is hard to break from, where our beliefs shape our perceptions, and our perceptions strengthen our beliefs.

Here’s an example that many of us can relate to. At one point in your early life, someone may have been told that you weren’t very good at something, soccer, for example. You played it because you enjoyed running around with friends and kicking the ball. But at some point, someone told you that you always missed the net and someone else would be better off playing your position.

Suddenly that statement becomes a truth that we internalize and chew on. We start to believe that maybe they were right… perhaps I’m not that great, and I should sit the next game out to let the better players play.

Because this hurts us, our brain instinctively wants to protect us from feeling this way. Self-limiting beliefs take root; we believe we’re incapable or unworthy.

The good news is that beliefs are not set in stone. They can be challenged, reframed, and reshaped.

The Iterative Mindset Method

Facing the fear of failure requires an adaptive approach – one can move and flex as our journey undoubtedly will. The Iterative Mindset MethodTM is a neuroscience-backed method that encourages us to take small steps toward our goals every day. It’s a better way of setting goals, where success isn’t measured by whether or not you achieve a specific outcome, but rather…(perhaps define what success looks like within the IMM)

It teaches us to accept that change is constant and fosters a willingness to pivot when needed. By iterating, we can take a practice-and-tweak approach to success. And so long as you stay in effort, you can’t fail.

Start Fresh With Fresh Tri

To overcome our fear of failure, we must reframe it. We can take hold of our self-limiting beliefs and create lasting change by rewiring our minds to use an iterative approach to our health and wellness.

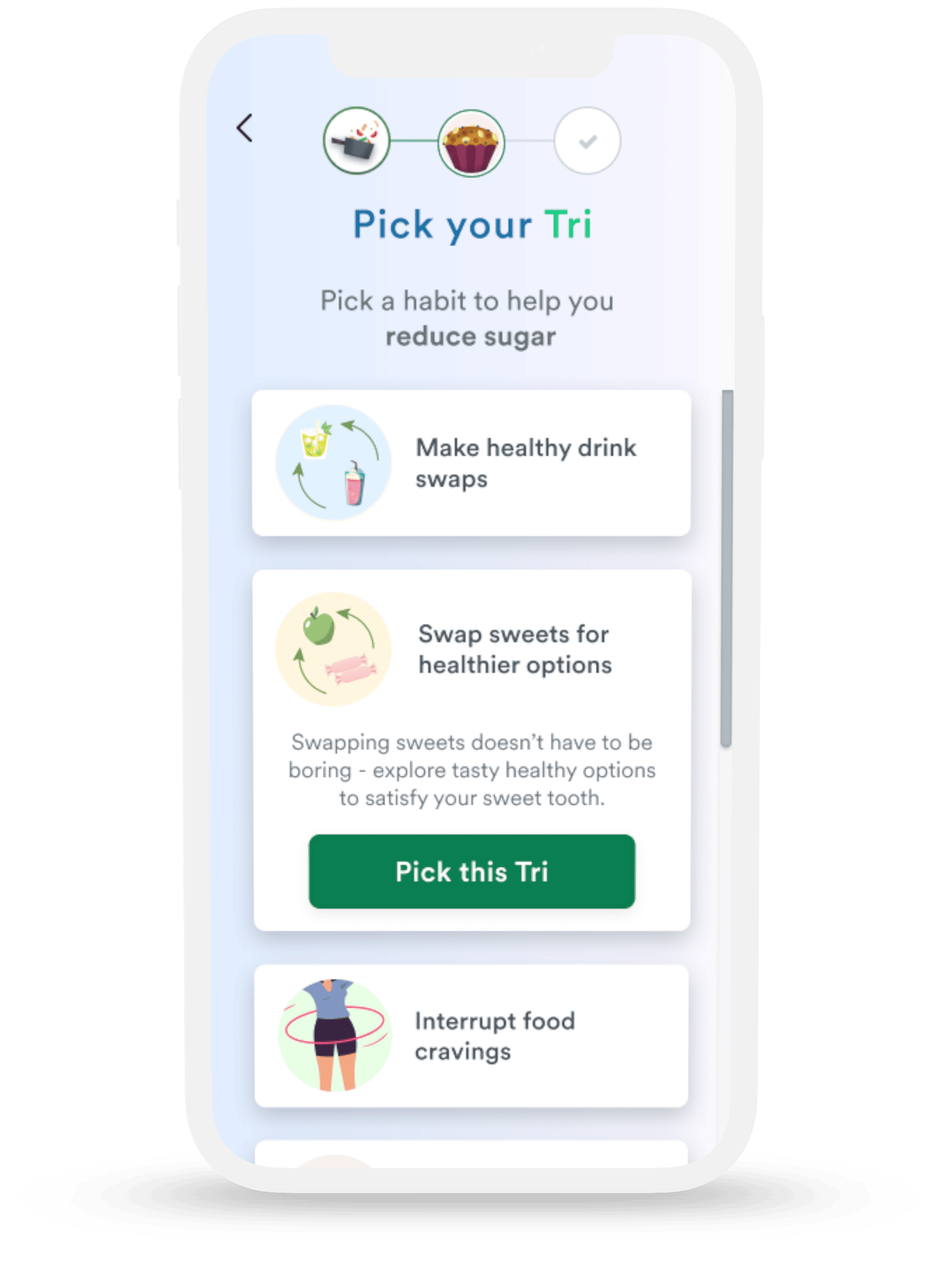

Your health and wellness journey doesn’t have a terminal end; it’s a lifelong journey. To support you along the way, we designed the Fresh Tri app, which leverages the Iterative Mindset MethodTM – made specifically for the habenula. This tiny brain structure stands in the way of us stepping outside of our comfort zone and challenging the self-limiting beliefs we hold.

Download the Fresh Tri app today and iterate your way to lasting health and wellness. “Failure” doesn’t stand a chance.

References

- Sosa R, Mata-Luévanos J, Buenrostro-Jáuregui M. The role of the lateral habenula in inhibitory learning from reward omission experiences. eneuro. Published online May 7, 2021:ENEURO.0016-21.2021. doi:10.1523/eneuro.0016-21.2021